Discord’s chat messages support both markdown and direct mentions of users, roles, channels, and various other entities. Detecting and rendering rich content in messages is a more complex challenge than it may appear on the surface.

This post will detail how our clients detect and render markdown and entity mentions in messages. In particular, the Discord Android app required a homegrown solution to maintain parity with the Desktop and iOS clients. As a result, we’ve open-sourced SimpleAST, our Android parsing and rendering solution. Read on to learn more about Discord’s approach to rich messages, and how we solve this challenge on Android!

simple-markdown to the rescue

One issue of particular interest is the case of entity mentions, i.e. direct references to users, roles, or channels. In these cases, we want messages to reflect name changes. For example, a message may mention me: @AndyG. If I decide to change my name to xXSSJ4AndyGXx, this old message should now render as @xXSSJ4AndyGXx instead.

To accomplish this, we avoid sending @AndyG as raw text in the message. Instead, we send <@123456789>, a reference to my user ID. This puts the burden on the receiving-end Discord clients to detect mentions in messages, and transform them back into the appropriate username when rendering the message.

In order to do so, our clients need a parsing + rendering system that that satisfies three major requirements:

- Extensibility: the system must detect basic markdown (like *italics* and **bold**) as well as artisanal strategies like the @User mention described above.

- Structure: the system should lend structure to the otherwise unstructured raw text. With structure, the messages can be inspected and post-processed as we see fit.

- Performance: gotta go fast.

We found a solution in Khan Academy’s open-source simple-markdown library. The web, desktop, and iOS versions of the Discord app are all written in JavaScript, so simple-markdown could be used directly.

The simple-markdown process looks like this:

- Clients define a list of rules which define the various formatting and entities (like an @User mention) that can appear in text. This meets our extensibility requirement.

- The simple-markdown parser uses that list of rules to transform raw text into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). This meets our structure requirement.

- The generated AST is then passed into a renderer, where it is transformed into some format that the client can display and interact with.

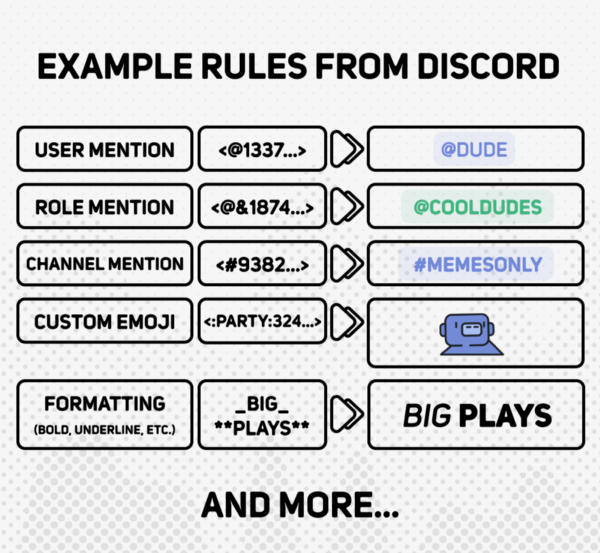

By adding our own rules, we can support various types of rich content in messages:

Do Androids Dream of Feature Parity?

simple-markdown worked great for the Discord desktop and iOS clients, but left our Android app out in the cold, since our Android app is built natively, not React Native (as discussed in a previous blog post). Without a parser of our own, we could still easily replace entities like @User mentions with a find/replace to detect <@123456789> occurrences when rendering the message. In fact, the Android app functioned like this for some time in 2016. Certain problems proved extremely difficult to solve, however:

- With our naive regexes on Android, there were many rendering inconsistencies between the Android app and our other clients. For example, formatting (like **bold**) worked inside of **code blocks** — it shouldn’t.

- We were not able to directly port the parser rules from the Desktop client. Any time Discord added a new rule, we had to worry about introducing weird edge-cases on Android, or at least losing parity.

- Discord’s desktop search feature allows for structured query parameters like from: AndyG#0001 (among others). We were about to implement search on Android and we knew that leaning on a robust parser would make it easier to detect and use such structured parameters.

The writing was on the wall: if we were going to maintain parity without excessive engineering effort, we were going to need our own version of simple-markdown that ran on the JVM to power our Android app.

The One Where Chandler Explains Parsing

Remember that the system we wanted would need to do two things:

- Parse raw text into an Abstract Syntax Tree

- Render that AST as text on Android

We’ll focus on parsing for now. Remember the three components that constitute the parse step:

- Node : a node in an AST which can have children. This defines how we represent an AST in code

- Rule : a rule which defines what types of nodes are generated by what types of text

- Parser : using a list of rules, takes raw text and turns it into a collection of nodes

Note that the Parser processes the input left-to-right as rules are matched. To support that, a Pattern that defines a Rule MUST only match with text at the BEGINNING of the source. This is why we include the ^ character at the beginning of all of our Rule patterns!

Hello StackOverflowException, My Old Friend

Our Rule interface required each Rule to return a Node with all its children already parsed and populated. To accomplish this, many Rule instances were calling parser.parse() on the text they were inspecting. This algorithm was simple to understand, but meant we could recurse arbitrarily deeply if we nested formatting. In other words, nest enough formatting in a message, and you could trivially crash the app by causing a stack overflow!

We needed Rule instances to contribute their information to the AST without recursively parsing their content. We solved this by having each Rule return only a single top-level Node. If it was a non-terminal Node (like a bold or italics node), it would also specify start and end indices that inform the Parser what slice of the original input needs to be parsed to supply that node’s children. In other words, our rules now return both a Node and a potential “deferred parse” specified in a ParseSpec class.

This allows us to change our parse strategy to use an explicit 🥞 stack 🥞 that tracks what parsing still needs to be done. The stack typically does not grow larger than a few elements in practice, as new ParseSpec instances are used immediately. For implementation details, see the source code here.

Performance Analysis

The app functioned with this parser for a very long time. We still noticed a little chug on older phones (which represent a significant portion of our user base), but it wasn’t immediately obvious where any performance improvements could be squeezed out of the parser.

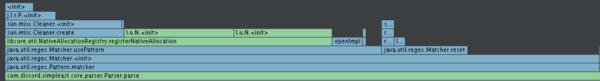

We used the Android Profiler (introduced last year in Android Studio 3.0), which provides a flame chart that aggregates method calls into a readable form that makes it easier to see where you are spending your computational time. We noticed that a lot of time was spent in the method Pattern.matcher(), which creates a new Matcher instance:

It appeared that most of our time during a parse was actually spent inside of Matcher.<init>, in particular in Matcher.usePattern, with some time in Matcher.reset. It was strange to spend a lot of time here — why were we creating so many Matcher instances? We looked around for initialization points of Matcher, and the culprit lay in this line of theParser:

// Create a new Matcher instance for the source being inspected

val matcher = rule.pattern.matcher(mutableSource)

Instantiating a Matcher every time we want to use a rule to inspect the text was expensive and, as it turns out, unnecessary:Matcher has a method that is specifically designed to allow a single instance to be reused multiple times on different sources.

Up until this point, we had bundled Pattern instances inside our Rule objects. Thanks to the Android Profiler, we identified this issue and began bundling prebuiltMatcher instances instead:

// Use the existing Matcher, just point it at the new source

val matcher = rule.matcher.reset(mutableSource)

Using this strategy, we were able to see as much as a 2.4x speedup on certain real-world messages, depending on the complexity of the parse parsing needed to be done.

Warning: If Rule (and by extension, Parser) instances are shared across threads, multiple threads could reset the same Matcher to different source texts. Therefore, usages of a given Rule or Parser instance should be confined to a single thread.

Will it rend?

We’ve got an AST now with nodes that represent various pieces of text, styles, and other entities like user mentions, emojis, etc.

Rendering is a simple process compared to parsing. Android has a mechanism for building text with various styles: a SpannableStringBuilder. We create a SpannableStringBuilder and pass it to each node; they operate on the builder in turn. To facilitate this, a Node<T> in SimpleAST has the following method:

fun render(builder: SpannableStringBuilder, renderContext: T)

- In simple cases, nodes may simply append text to the builder, apply styles to the text in the builder, or make the text clickable or otherwise interactable.

- In more complex cases, nodes may specify a type T that provides information that they need in order to render themselves, ie.e. their renderContext. This could be something as simple as and Android Context so that the node can resolve resources, or it could be a data structure that, for example, facilitates the node looking up usernames for a given user ID.

Marching Ever Onward To Tomorrow

SimpleAST currently powers the Android app’s message rendering, and we’re happy with its performance, robustness, and extensibility. It also lends us the power to keep up with the fast-changing requirements of Discord as a product, since porting parser rules to Android is such a breeze.

That said, there are some opportunities we see with both SimpleAST and its use in our app going forward:

- Parse off the UI thread: We parse and render each message on the UI thread on-demand as the message rendered on the screen. This means that during fast scrolls, there can be a noticeable frame drop, especially on low-end devices. Instead, we could parse the messages at an earlier stage in the pipeline, on a thread pool dedicated to parsing these messages. The upside is that this would make the scrolling experience butter-smooth on all devices. However, if implemented naively, it could manifest as a longer load-time for batch messages loading. Intelligently implementing message parsing off the UI thread is one of the most exciting opportunities for performance improvements in the Android app today.

- Further SimpleAST performance improvements: We will continue to push more performance out of the SimpleAST library, with a helping hand from the Android Profiler.

We’re always looking for the next great addition to our engineering teams at Discord. If the problems described here sound interesting to you, and especially if you are a gamer at heart, check out our available positions here.

If you would like to use or contribute to SimpleAST, check out the open source project here.

.png)

.png)

Nameplates_BlogBanner_AB_FINAL_V1.png)

_Blog_Banner_Static_Final_1800x720.png)

_MKT_01_Blog%20Banner_Full.jpg)

.png)

.png)